FOF Best of 2018

Greetings fellow motion picture lovers!

Well, looking back today I realized that this is actually the 6th year of me blasting these lists out into the ether. You would think I should have learned a thing or two about film since their inception. Eh, probably not. But, I did just ascertain that gifts for a 6th anniversary include candy and iron. Perhaps this is a hint I should tackle my Ironman sooner than planned, or find a sweeter tone in this world of acrimonious voices. In any case, I’ll try to deliver the goods. 2018, while being a horror show for many, was actually FANTASTIC for film. Such a wealth of great pictures at home in the U.S. AND in different pockets of the globe. Narrowing this baby down was harder than it’s ever been before. (I was going to say “than going a day without encountering some rambling presidential tweet, random left-leaning article about his shirt, hair, or hand holding (or lack thereof), and articles on both sides shouting “DOOM!!” but see how I’ve grown! Oh wait…)

Anyway, I’ve come to notice that my “reviews” have really morphed and evolved over the years. Early on they were just about presenting short snippets of the ten pictures I liked the best that year. Now, I’m fighting to keep each of these from being full on review articles. I apologize if the length is a deterrent for you. At the least, you can just quickly scan the bold titles and check them out for yourself. If exposure to these is the only byproduct, I’m a-ok with that. In the future, I’ll be trying to use my Triguyunfiltered blog to do full write-ups for each film and then just link them on my year-end list page. I don’t know about you, but my life is generally surrounded with children just about all the time (Ahhhhh!). Triathlon and film are two of the main things that save me from the abyss. I write these words of love, however mediocre, with that in mind.

I hope you enjoy.

-Nick

#12 Crazy Rich Asians

Man, oh man, I loved this picture. It was just such a delight to watch. “If only someone could actually make a SMART ROMANTIC COMEDY!” a nameless cinephile shouts into the void. Well, wouldn’t it just turn out that you’d find it right here in this groundbreaking picture with a nearly entirely Asian cast. Sure, Crazy Rich Asians has some of the usual motifs of the rom-com genre. Boy meets girl. Boy must meet girl’s family (except it’s flipped here). One lover is hiding significant details about his past from the other. Girl has a funny childhood friend who provides the comic punch and the necessary deep breaths between the dramatic scenes. It’s all there in Crazy. But there’s also much more – a tale about class structures and cultural traditions old and new, expectations, and prejudices.

When Nick Young invites his girlfriend, a self-made woman who immigrated to the US with her bereft mother and now teaches at NYU, to his friend’s wedding in South Korea, she is excited but a bit nervous. She soon realizes, however, that she is entirely unprepared for what awaits her there. For what Nick has neglected to tell her is that he’s actually the scion to a family of extreme wealth, a bachelor sought hard by the high socialite circles from his youth. And at the head of this bastion of opulent domesticity stands his mother, a hardliner of the “old ways,” played absolutely masterfully by Michelle Yeoh. Yeoh stands for tradition and simply cannot have her beloved son, who she hopes will take the reins of the family empire, marrying some girl of questionable pedigree and anything but the purest bloodline.

So, the battle lines are drawn, and Wu must grapple with rising questions and doubts: Is Nick worth all of this? Can she really stand toe to toe with the matriarch who treats her so coldly? Does she have what it takes to assert her own strength and worth? Do dark secrets loom in her own past? The unfolding of this conflict is just great filmmaking. Power struggles and witty remarks are bandied about in the midst of glitzy set pieces and extravagant parties, as Nick must confront his mother and, in so doing, himself. By the time the third act rolls around we’re treated to the real worth of Crazy. This is not simply some ho hum dramedy swapping out mostly white characters for Asian ones. This is a film that transcends the trappings of its genre even as it borrows from its cliches. Witness firsthand the beauty of the friend’s wedding scene, the expansion of Wu’s quiet strength, and a final showdown between the two female leads that is unexpected, moving, and satisfying in equal measure.

#11 Eighth Grade

Ah, middle school. We remember it well, don’t we? The time of growth that it contained for us. Puberty (yikes!). Nascent feelings of independence and sexual curiosity. Moldable personalities taking shape as we search for the influences of media, adults, and peers who will tell us just who we are. But, do we really remember it? Really?? Or do we repress quite a few of the real life details because they’re just too painful, embarrassing, confusing, or just plain icky for us to recall them? Well, Bo Burnham would probably argue for the latter. In Eighth Grade, he makes the powerful statement that adolescence is a lot less like the joyful singing and dancing of High School Musical and a lot more like Captain Awkward Stands on the Brink of Adulthood (no, that’s not a real film).

Words that would be apropos in describing Eighth Grade are cringeworthy, painful, and above all, awkward. Far from the beautiful put-togetherness of the aforementioned musicals and the tightly boxed teen archetypes of the John Hughes’ master works of the 80’s (Yes, I love them too), REALadolescence is excruciatingly hard. And it is likely harder NOW than ever before. Still, Burnham strides confidently into this modern maelstrom, beginning his picture with a close-up of his protagonist, a slightly pimple-faced regular girl in her last week of middle school. She is, of course, filming something for social media (Duh! Who isn’t??) A series of YouTube videos, in fact, which portray a confident girl telling her peers all about how to “be yourself” and push out the bad influences.

When the camera stops rolling, however, we get to know the real Kayla. She’s shy, stumbles through her words constantly, can’t look her peers in the eyes (even when she has the moxie to confront one later on. Oh right, spoiler alert. Sorry.), is as unsure about boys as they are about themselves, and has the world’s most caring dad. This same dad (played expertly by Josh Hamilton) also, unfortunately, happens to be the world’s worst person at communicating just about anything. So, we sit back, we squirm, and we watch Kayla navigate scene after scene – talking to cool kids, attending a party, fighting with her dad, hit on by a neanderthal, meeting a helpful high schooler, dreaming of the future – on her way to finding her true self.

Burnham’s verisimilitude is as astonishing as his compassion for his heroine, who let’s face it, is/was really all of us in some way or another. There is no GRAND ending, no whiplash transformation, but there is evolution aplenty and some of the finest dialogue penned all year. The film also offers powerfully relevant observations on the golden handcuffs that are social media and the sense and care of self that it engenders in our youth. If you need more, watch for two things in the course of the film – the incredible musical piece by Anna Meredith as Kayla enters the party and a scene between Kayla and her father late in the picture. It is here where the facade finally comes down, Kayla at last admits to herself what we’ve seen in her all along, and Mark recognizes the power of presence and finally finds a few authentic words to help her on her journey. Maybe we don’t want to remember these years of our lives. But then again, maybe a journey this authentic is well worth the ride.

#10 A Quiet Place

A genre picture on your list? Seems a little dicey, Furman, don’t you think? Maybe it is. But, the fact remains: in A Quiet Place, director John Krasinski (yes, the same Jim Halpert morphed into Jack Reacher by way of a Mandy Moore rom com and a Michael Bay hoo-rah John Krasinski) accomplishes a truly remarkable feat. This is his FIRST time behind the camera, and yet he shows no signs of beginner’s angst. Instead, he finds an incredible ability to strike such a delicate balance – a monster thriller with post-apocalyptic hues and a wholly unique concept (or rather a very ANCIENT one) of wordless storytelling. Yet, all of this is really just the shell, the husk which carries around the true tale about the power of love and family and the honor of sacrifice.

Krasinski nails the former bit dexterously and intricately. Do not be misled. The suspense in this film is REAL, despite the fact that there is probably less than 10 lines of dialogue throughout its running time. The shots are tight. The sound editing and camerawork adroit. The performances perfectly measured. In fact, there is a real touchstone of Hitchcockian filmcraft at play here. By that I mean the ability to create suspense through suggestion, tautness through the presentation of fewer details which then allows the viewers mind to wander, explore, and fill in the gaps with rising horror. These kinds of works pull at us psychologically, extracting our fears scene by scene until we find ourselves so entrenched that the ridiculousness of a tale about creatures who destroy the world through over-sensitive aural capacities is completely lost on us. By the end, we know only one thing – we must survive! This is the beauty of A Quiet Place.

And yet, it is not even close to ALL of the beauty of the film. Nestled in the middle of all this budding suspense are signs of familial disquiet. A deep-seated pain for a family member lost. A daughter crushed by the burden of guilt over a horrible mistake, leaving her feeling that she is neither loved nor lovable. A mother willing to go to any lengths to protect her children and the life growing inside her, and finally a father so hellbent on survival (he must keep them safe and alive), yet carrying around such ruefulness that he finds little means for sharing his care. Without providing any spoilers, these relational issues come to a head in one of the more powerful endings in recent memory – an ending which wraps up the suspense and thriller plot strands while showing the incredible redemptive power of love. Don’t be fooled by teasers or posters. A Quiet Place is a fantastic family tale (though I’d put the younger kids to bed before pushing play).

#10b Revenge

Look, to be honest, I don’t know if this film really belongs on any year end lists. I’ve relegated it to a (b) spot to honor that fact. But, literally no one (hipster literally, not really literally) is talking about this film, and it’s ridiculous! Why? Because it’s a flipping great horror story! France has been killing it in the world of horror the past few years (see Raw from last year), and it’s time the world noticed. Just the set up in this film alone is dynamite. It starts as one thing and ends up as something different entirely. This is an exploitation flick at heart. So what do those have? If you answered beautiful, scantily clad girls you would be correct. Traditionally, women are weak in exploitation pictures. They’re in need of rescuing. They are largely objects. This practically lends itself to a classic trope of the genre – the rape-revenge tale.

And so Coralie Fargeat, the female director behind this work, obliges us in the beginning. She presents our protagonist in a bathing suit fawning over her wayward lover and has the camera do long, slow pans around her frame. It’s cinematography out of something like Into the Blue (there’s a journey backwards not worth taking!), and when Fargeat at last lets a shot linger on Matilda Lutz’s posterior for a few counts too long, we begin to sense that something else is going on here. So, the picture then twists and turns through Lutz’s fantastic damsel to her victimhood at the hands of perverse men. There is only one problem – when they leave her for dead at the edge of the desert, her heart is still beating.

After a few long minutes on the brink, she begins her journey back and all of the violence, gore, and visceral revenge you would expect from such a picture comes to pass. Alone, Lutz has no man to save her, but it turns out this damsel doesn’t need one at all anyway. Her rampage is satisfying and yet, while stretching the boundaries of biology at times, it is also informative. Fargeat’s camera work now focuses on Lutz’s face, her resolve, her warrior-like toughness and spirit. Her makeshift costume is vastly secondary. We watch with a sick kind of glee all the way up to what I would argue is the strongest final five minutes of a film this year. It’s worth checking out for that alone. But, it’s also worth seeing because, in Revenge, Fargeat gives an appropriate feminist gut-punch twist to a genre long up for dispute.

#9 You Were Never Really Here

A hard-hitting deconstruction of the blood-soaked Hollywood hitman revenge thriller, You Were Never Really Here subverts audiences expectations of and desire for violence at every turn. Joe (Joaquin Phoenix) is a man teetering on the brink. Plagued by the kind of past trauma at work and home which could be the ruin of ten men – childhood abuse at his father’s hands, PTSD from haunting losses in the Gulf War, failed rescue attempts as an FBI agent, and forced care of an elderly mother, all revealed episodically in expertly spliced edits – Joe routinely longs for the end. He often images himself committing suicide in lavish ways, with the world around barely noticing.

Still, he manages to hang on and keep his personal demons at bay. Instead, he embraces a life of violence that manages to still be a tad philanthropic, rescuing missing girls from their traffickers and becoming a specialist in the art of killing. As such, our protagonist is soon hired by a state Senator to track down his missing daughter. What at first seems like a straightforward job soon grows to be a personal hell, as Joe must contend with a growing conspiracy whose tentacles reach some very influential people. The audience is soon left to wonder, will this finally be the end for this hammer-wielding man with a beating heart, or will he once again find a way to save the day.

I believe that I have seen a slew of movies LIKE You Were Never, but none with such an incredible balance of visual pizzazz and existential depth. Intense vigilante hitmen pics simply don’t go with slow burn indie character studies. Yet this is precisely what we have here, and Lynne Ramsay, who adeptly helmed this entire project, demands that we question the very movie for which we’ve been set up. Never before have I seen a film so obsessed with violence which actually visually portrays so little of it. Nearly all of the killing is kept off screen or purposefully out of view of the audience. Do we actually see Joe kill anyone on screen? Even the powerful sequence where he infiltrates a building running a full sex trafficking operation jumps between fixed shots of various hallway cameras, edited in a kind of disarray which makes seeing anything difficult. Ramsay’s message is quite clear: Joe’s violent talents are not a showcase for entertainment. This is one revenge thriller that does not celebrate its mayhem.

Before concluding, let me quickly point to two powerful moments contained in this journey. I stated before that Ramsay has all the highly stylized features down pat (think Drive or something equally sleek), and we really catch this in a sequence where Joe buries a body in a lake. After doing so, a sequence is initiated where he dreams of drowning himself before the missing girl’s face pulls him back to reality. Notice all of the incredible visual details of that scene. The other points to the remarkable humanity of Phoenix’s character (By the way, if you ever wished for an opportunity to have Joaquin Phoenix’s merits as a character actor proved definitively, then this picture is it). After being attacked yet one more time, Joe is able to overcome his assailants and leave them for dead. Yet, rather than exiting the scene immediately, he lays instead next to the dying man and engages him in a final conversation. The two even touch hands as they recognize the sliver of humanity between them. In the end, this is really the true staying power of You Were Never Really Here – a methodical examination of genre, violence, and the visceral appeal of empty bloodshed which nonetheless contains richly, human characters.

#8 First Reformed

Be forewarned; First Reformed is by no means a film for everyone. If the viewer is not turned off by the complicated rumination on the nature of faith, the environment, and personal responsibility, the muted aesthetics or talky screenplay, then perhaps the surrealistic sequence which closes the film will be its undoing. Yet, for those who gut out this intense soul journey, the dividends are rich. Reformed is a story of a parish priest, Ernst Toller (played by Ethan Hawke in a career best role) whose church is about to turn 250 years old. A once thriving stop on the Underground Railroad, First Reformed Church is now little more than a local tourist trap, shrinking in the ever-expanding shadow of the megachurch down the block.

The inciting action of the film comes when one of the few faithful parishioners of Toller’s church (Amanda Seyfried, also doing her best work) approaches him with a humble request. She’s pregnant and her husband is having a crisis of faith about keeping the child. Toller dutifully agrees to meet with the man, and what follows is one of the more quietly powerful film dialogues of the year. The husband is plagued by doubts, as he sees a world on the verge of environmental disaster and fears greatly to bring an innocent newborn into that fray. Toller is merely able to offer a few perfunctory remarks which offer little solace before departing to his own thoughts, a journal which is read as a voiceover to us throughout the film. As the plot proceeds, and Toller’s entries become more frequent and dismayed, he begins to take on the cause of the husband. Through new eyes, he glances the corporate greed around him as well as the political maneuvering which the success of his parent megachurch seems to necessitate. Soon, Toller begins to unravel, leading him down a dark path which could end in one act of profligate violence.

So, look, there are numerous criticisms about First Reformed which I feel seem to miss the mark. (And some which do not. Notice, I DIDN’T make it #1, people!!) Folks have rightly called the film to task in several regards. They are incredulous about a sincere man of faith really coming unwound to this degree. Would such a man really be capable of this kind of violence? Others claim the corporate connections to megachurches are overwrought and untrue. Still more despise an ending which really could leave one asking: “What in the world JUST HAPPENED?!!” I will leave it to the viewer to draw their own conclusions about this work. It surely does take wild, unexpected, and uncomfortable turns in its final act which will shock some, anger others, and disturb, well, everyone.

But, let me just say two things in its defense. The first is this – What did you expect when you sat down to watch a Paul Schrader film? This is the writer of Taxi Driver and the director of American Gigolo. Any of those central characters ring a bell? Schrader has practically made a career out of analyzing the fractured psyches of male souls grappling with the potential for violence as a cathartic response to chaotic environments. Moreover, it’s subtly clear from the outset that Toller has been plagued by past demons, such as a son lost in war, personal sickness, and mounting alcoholism. Two, and more importantly, can we just freaking appreciate the tour de force that is Ethan Hawke in this movie?!! He is the center and lynchpin of this whole enterprise, and his exclusion from the list of best actors nominated for the Oscars is a complete crock. First Reformed is a picture anchored by a a commanding and quietly revelatory performance by Hawke, a uniquely remarkable script by Schrader, and a filmic tone which matches its lead – brooding, muted, subtle blue hues, shot in the old square box Academy ratio. “Who can know the mind of God?” Toller muses in the film’s central scene. Indeed, it is in Toller’s outworking of this query that First Reformed most powerfully takes hold.

#7 A Star Is Born

One does not need to look too far or cogitate long on why a picture like A Star Is Born belongs near the top of the heap on best film lists for the year. A talented and established actor finds a Southern twang and picks up a guitar. A renowned pop star goes “meta” and shows off her acting chops. An aging legend with one of the most distinct deep drawls of all time signs on as the singer’s brother. And the music…man the music. Don’t let this soundtrack bore itself too deeply into your skull. You may find that it resides there for a LONG time.

In truth, I have a bit of a love/hate relationship with A Star Is Born. It has one of the strongest first hours of any film in recent memory. The burgeoning love story between Jackson and Ally is just so beautiful, heartfelt and ALIVE that we can’t help but be swept up in its romantic embellishments. The rise of their relationship is soulful, well-paced and matched perfectly to the stage life and songs they share together. Yet, as these two artists come together and Jackson’s wizened experience breathes life into Ally’s once dead career, inevitable conflicts rise to the surface. This is especially true given Jack’s love of the bottle and seeming inability to maintain the reins of control in his own life.

So begins about midway through the picture what is, to me, one of the roughest 45 minute stretches of an otherwise great film all year. The issue is not the conflict. The complex journey of finding love and keeping it through the rigors and pitfalls of stardom is nothing particularly new. The problem is that the storytelling just gets downright questionable. An apparent meta sequence involving Gaga and SNL is only the beginning. There is also the unfortunately laughable Grammy Awards scene which goes for “empathy towards an addict” and lands on “so cringy you want to run and hide” instead. Beyond this, there are many derivative elements – Cooper’s borrowed accent and addiction from The Dude in Crazy Horse, another huge plot inclusion which gives too much away to speak of here (but is nonetheless TOTALLY unnecessary), and many others. Finally, we have the worst part of the whole ordeal, Ally’s music manager, who is so ridiculously two-dimensional and spouts such on the nose acidity that he belongs chopped up on the floor of a failed USC film student’s room rather than anywhere NEAR this awards contender. His inclusion and lines are nearly unforgivable.

BUT, let us remember what is so great about A Star. A tale about beauty and heartbreak, a courtship fighting for its own life, it is at once poignant and gut-wrenchingly tragic. Scene after scene sticks with us. Jack and Ally’s first spontaneous rendition of “Shallow” in the parking lot of a grocery store, to it’s opening to the world on tour. An incredibly authentic and devastating fight sequence between Jack and Ally in a bathtub. Or, how about my REAL Oscar favorite in best supporting actor, Sam Elliott sharing a heartrendingly tender moment with his brother in a truck. Andrew Dice Clay and Dave Chappelle offer fabulous cameos as well. But perhaps all of this pales in comparison to the final few scenes, where tragedy is made auditory in the form of a monster ballad the likes of which only Gaga could deliver. In the end, what we have is a mixed bag of goods – a first time writer and director who takes bold risks, proves remarkably deft in production and cinematography, and gets award-worthy performances which JUST overcome poor story elements and reclaim the power of A Star’s opening scenes.

#6 The Favourite

I have long been a Yorgos Lanthimos admirer. His films inhabit a world and space wholly their own – delightfully odd, surreal, tonally distinct, and darkly comic in the most sinister ways. I first fell prey to his peculiar guiles in Dogtooth, a picture about a set of parents who had chosen to raise their children in utter isolation from the outside world, complete with Kafkaesque horror and mordant wit in equal measure. Between that picture and The Favourite, Yorgos has only honed his craft and clarified his vision. Most notably, he has come to specialize in the use of deadpan humor in a way that makes the bizarre seem commonplace. Because of this, his pictures twist and turn around very loose storylines, and the unexpected can (and often does) happen at a moment’s notice.

Thus, on THIS particular Lanthimos joy ride, we step into the world of 18th century England and find a tale which vaults between period piece and parody, making it a bizarre confection in many ways. If you’d give me simply one phrase to describe The Favourite it would be: “chock full of razor-sharp wit,” only one word – “brilliant.” The first thing to revel in is the airtight screenplay, which is flat out hilarious. This is all the more impressive because it is penned by two other writers (Deborah Davis and Tony McNamara) and yet enfolded into Yorgos’ grander vision. Witty one-liners and curt insults abound, as well as nutty sidebars which somewhat break the fourth wall. The overall effect is to create a sense of anachronism, whereby this is a picture about times long gone AND the trappings of power today.

The zingers fly by the viewer like a Sorkin script and yet the direction takes us to a different place. To wit, the film features a very engaging score which comes to life just as the dialogue subsides. Moreover, Lanthimos employs fish-eye lenses and stationery cameras on a pivot to increase the sense of tightened space or even the claustrophobia of the royal kingdom. It turns out not even a giant castle is room enough to escape one another when personalities are this large.

Speaking of larger than life characters, The Favourite has three such ladies vying for their own positions of supremacy. THIS is the real unparalleled merit of the film. I don’t remember seeing a film in recent memory which featured three such assured performances, and a cast that was so nearly perfect in every way. Each of the women simply nailed their roles – Weisz as the REAL power behind the throne, influencing the Queen to forward her own bullish policies, and Stone as the doe-eyed newcomer to the scene who will do anything (and I mean ANYthing) to raise her social position to its former glory. Yet both women are perhaps outshined by Olivia Colman as the near schizophrenic Queen Anne. She is fawning and loving one moment, impetuous and childish the next. Again, cowed and playful, then mercurial and defiant. Together, they are unmatched in a cast this year.

Despite all of these strengths to recommend it, The Favourite did feel a little light on story to me. There are plot strands and hints of backstory that are eluded to at times, but I found the viewer to be a tad short-changed when looking at the narrative as a whole. But this could be a broader criticism of Lanthimos in general, who is more concerned with the idiosyncrasies of human nature and their interactions then big plot payoffs. Moreover, and this is why the film is not higher for me, there is no one to really root for wholeheartedly here!! These people are, quite frankly, despicable. They are unapologetic in pursuit of their aims, which is itself a strength, but go about the business of this in the most diabolical and dastardly ways. Even Lady Sarah, who is the “fall” portion of this rise and fall saga, can only engender so much empathy in her audience. So, I would conclude that The Favourite is just about perfect on a technical level, but in terms of substance, slightly lacking.

#5 Burning

No other film in 2018 captured the critical importance and concrete ability of the elements of moodand tone to set the trajectory for a picture like Burning. If there is ONE picture that I could impress upon you to watch which is perhaps lesser known state-side, it is this one. Get over the subtitles and moderate pacing. This story will drill itself into your brain and stay there loooong after the credits roll. It will patiently entrap you in its psychological puzzle and leave you no choice but to ride its simmering suspense until the very end. Afterwards, you’ll think you have it, but you’ll still spend hours (ok, maybe minutes) debating the flip sides of the ending revelation, until you eventually conclude that your leagues away from being sure of it at all.

For a film so bedazzling, from a plot perspective Burning is really quite simple. A young millennial in South Korea bumps into an old childhood friend (Hae-mi) while out making deliveries. After a rather uninspiring night of “catching up,” she tells him that she’s going on a trip to Africa and asks if he’ll watch her cat while she’s away. Jong-soo, believing that he’s beginning to develop feelings for Hae-mi, somewhat reluctantly agrees. The only trouble is he never seems to meet the cat. Soon, Hae-mi returns with a new friend she met on her trip – Ben. As they hang out together one evening, Ben reveals a certain secretive pyrotechnic hobby. This all seems harmless enough…until Hai-mi goes missing.

Burning is really a slow-burning character study locked inside a mystery thriller. It is littered with clues which pass our eye unceremoniously and then come rushing back in the wake of the film’s conclusion (see: mysterious cat above). It is ultimately a story which presents us with three characters, and then fills in their portraits with little brushstrokes here, a couple of revealing lines of dialogue there, etc. We think we get to know them, but there are other matters at play in the background. Like the contrasts between Jong-soo’s working class background with absent family members and Ben’s posh urban lifestyle and close relations (at last at face value). Or, Jong-soo’s unsure demeanor and meek vocal delivery vs. Ben’s aplomb and almost eerie ability to be on top of everything. Soon, these differences will cause Jong-soo to begins checking up on Ben’s proclaimed hobby to see if it’s real or a front for something more devious. This eventually leads the two men into a showdown of sorts which will leave you breathless.

Thinking about those two characters, I’d like to finally say a word about the acting in this picture. If you’re like me, Steven Yeun is the lovable Glenn from The Walking Dead. Maggie’s magnanimous beau. After this baby, that image of him is blown to smithereens. This dude has flat out CHOPS for days, and in his native tongue, he is a force to be reckoned with. Similarly, in an entirely different role, Yoo Ah-in, imbues Jong-soo with just the right touches to create a man who appears weak and lacks confidence in his abilities but still has much brewing under the surface. I’ll end this review like I started. Mood is just SO important in Burning and Chang-dong Lee uses an almost spooky, minimalist score alongside the aforementioned performances (not to mention Jong-seo Jun’s terrific turn as Hae-mi) and breathtaking cinematography to create a slow-burning (pun intended) masterpiece. Be patient, viewer. By the finale, your expectations will be subverted, your investment richly rewarded.

#4 If Beale Street Could Talk

I’ll admit when it comes to love, I’ve grown to be a bit of a cynic. Neither is there enough space to explain the reasons why this is in detail, nor do I have the applicable counseling fees I’d be paying you to do so. At any rate, while my most beloved love films of yesteryear were in the hopelessly romantic, Nicholas Sparks-ish vein (only without all the damn dying!), I’ve grown to appreciate the truly authentic side of romance. Perhaps it’s going on 14 years of marriage, or just becoming shrewd to the “ways of the world,” but my more recent faves march to the beat of a different drum (think Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind or The Before Trilogy). Given these truths, it would seem far more likely that Cold War would be here in place of Beale Street, a film which is after all really about the power and moving depth of young, innocent love. But I must confess, I fell for its charms hook, line, and sinker. Tish and Fonny’s love may be naive, inexperienced, and therefore unsullied, but it is also forged in the fire that only comes through righteous strength. A fortitude developed in the face of racial prejudice and near impossible odds.

Next to A Star Is Born, this is the strongest opening 30 minutes of a film all year. Director Barry Jenkins continues his meteoric rise in cinema by deftly sticking to the novel’s source material, utilizing the vernacular of Baldwin’s novel in nearly every scene. This creates a sort of high art, stagy air in the film – like we’re watching a fantastic theatre production. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the film’s best scene – a reveal, if you will, of Tish’s pregnancy to first her own supportive and loving family and then Fonny’s tumultuous kin. The dialogue is simply unreal in this scene. It contains some of the best lines of the year, is in turns riotous and shocking, and creates well-rounded profiles of the film’s leads.

Another incredible event is the film’s lone moments with Brian Tyree Henry, playing Daniel, Fonny’s childhood friend who is fresh out of prison. Daniel spent two years in the slammer for stealing a car after cops convinced him to take that rap over a marijuana charge, even though he doesn’t even know how to drive. Over drinks, the two young men catch up and reminisce about days past. Finally, Daniel admits to the horrific treatment he received in prison and the fear that gripped and controlled him. To my mind, this is one of the strongest few minutes of work by any character actor this year. Alongside his work in Widows, Henry proves himself a real acting dynamo. It’s a shame the Academy failed to notice.

Backtracking a bit, we learn early on that Fonny has been in prison for the rape of a Puerto Rican woman, which he did not commit. Rather he was singled out by a racist cop looking for some vengeance (we gather this through another moving sequence later on in the film) and a traumatized woman simply looking to pin the blame somewhere. It is in this light that we see the greatest strength of If Beale Street Could Talk, namely that it works on SO many levels. It is a dash of timeless romance, a dollop of family drama, a drop of legal intrigue, and a pound of incisive social commentary. This is a powerhouse recipe for success. Beale Street itself, as the opening credits tell us, is a reference to the black neighborhoods of the time, where jazz was born and folks stood together to make a way in life. Jenkins employs his own jazz-like flourishes, building his tale around a few key scenes (the three I’ve mentioned and another which features the young couple imaginatively apartment decorating in a undeveloped building for rent) and a host of little bits of information from different stages in these characters’ lives sprinkled throughout the narrative.

Tish and Fonny’s love is one born of mutual respect, integrity, and years of friendship, for the two grew up together (even sharing a bathtub as children). Thus, even their first time together intimately is depicted with such poignancy. It is a love that we rarely see portrayed with such profound depth inside or outside of the genre. It is because of this lifelong connection that Tish and Fonny are able to maintain their unbreakable bond, even as they are separated by society’s prejudices, wrongful accusations, and literal glass and bars. Those are the reasons why I could “buy” such a pure presentation of love. And all along it seems that their families could see it too. Near the end, this is what inspires Tish’s mother to travel to Puerto Rico to try to clear her future son-in-law’s name with the accuser (in the scene that will probably win Regina King her Oscar). In sum, it is an incontrovertible truth – Beale Street is a picture which goes soaringly high to spite a prejudiced world dwelling way down low.

#3 Blindspotting (2018)

Truth be told, for the longest time I debated making this film my number 1. No other one just reached out and grabbed me like Blindspotting did. And, as pictures sometimes do, it came completely out of nowhere to captivate me. I went in with super low expectations and was simply blown away by this tale which blends mismatched buddy comedy with trenchant social and racial commentary to exquisite effect. I’ll put it like this – of my 10 favorite scenes of any film all year, probably 4 or 5 of them are in this movie alone. Yeah, it’s that good. But it’s also nowhere near perfect – it’s kind of messy tonally, bounces around a bit, is overstuffed with ideas in that first time director and writers kind of way, and the like. Still, it never stops swinging for the fences on issues like racism, gentrification, police brutality, the justice system, and corporate branding, attacking them with wit and swagger and, more often than not, knocking them out of the park.

Collin (played by the fantastic Daveed Diggs) is on probation for getting caught up in a situation he’d rather move past. He’s been an ideal citizen for the first 362 days of his mandated yearlong service, working by day as a mover alongside his best childhood friend (the dynamic Rafael Casal who co-wrote the screenplay with Diggs), adhering to nighttime curfews, and staying within Alameda County at all times. The two men have a natural chemistry because they’ve grown up in Oakland together (both in real life and in film) and watched the neighborhood morph and gentrify at an alarming rate. Collin has done well thus far, but maintaining his focus and calm during the last three days will prove far more difficult.

While on the way home from another night hanging with Miles, Collin unwittingly gets himself caught in the crosshairs of a police chase, and he soon witnesses the fatal shooting of an unarmed black man at the hands of a white cop. Though he quickly returns home, Collin is increasingly haunted by the incident, depicted masterfully as a series of dream vignettes (or rather nightmares) where he has to contend with judges, juries, and dead members of his own race. His sense of guilt for not standing up against the oppression he witnessed is delicately pitted against his desire for a do over in life. At the same time, Miles, a walking over-compensation – a white guy who wears a grill and is ready to fight anyone who invades his turf – becomes distraught by the gentrification of Oakland, and the resulting sense of loss of identity and home it brings him.

Soon, the changing social landscape exposes the disparities between them. Tension begins to build between the two men, and they struggle to maintain the camaraderie which once came so easily to both of them. Events occur which bring this simmering tension to a boil. First, there is a party scene where a young hipster black man mistakenly misinterprets Miles’ entire persona as cultural appropriation and calls him out for it. Miles, who is actually a proud street member of the “old Oakland,” will have none of it. The two tussle and during the altercation, Miles begins waving a gun around he purchased under the auspices of protection. Collin, furious with his friends’ loose-lipness and reckless behavior, finally calls him to task in the most explosive argument of the year. That scene is simply incredible. There are four of five quotable lines of dialogue in it alone.

Still another scene relates the meaning of “blindspotting,” when Collin is talking to a former girlfriend warning him to be wary of Miles’ influence. It is essentially an image which can be interpreted in different ways, but the individual is only able to see one of these construals. Again, quote board material everywhere. This leads us to the finale, essentially a piece of performance art which has more in common with Diggs’ Tony-winning work in Hamilton than anything on film. In it, he finally confronts the demons which have been haunting him in a brilliant monologue that is simply unrivaled. But this is what Blindspotting does so well throughout. It takes a buddy stoner comedy and flips it on its head. It employs classical music as its overtures, rather than gangster rap, and reads more like a stage play than a film about “the hood.” It’s high art for low times. If you’re putting Black Panther or BlackkKlansman on your year-end list in 2018, then you NEED to see this movie.

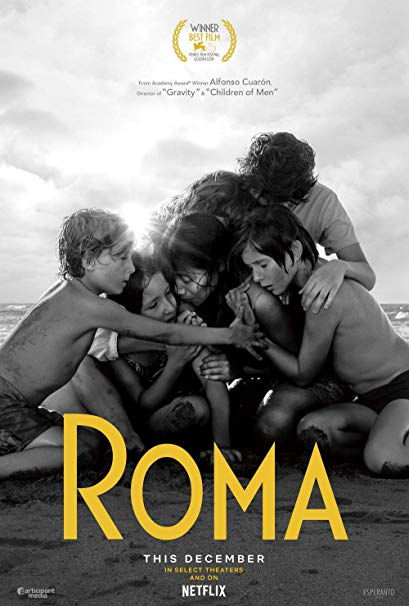

#2 Roma

There has probably been more written or said about Roma than any other film in 2018. It has become a lightning rod for broadly disparate commentary – from those calling it long, slow, bougie and unworthy of its shining accolades to others foretelling its rise to the top of any decade film lists for the 2010’s. I am personally going to argue much more strongly for the latter, though I sympathize with the critiques of the former. Let me just rip the band-aid off and say it straight away: Roma IS the BEST picture of 2018. Taken in sum, the argument is almost indisputable. No other Best picture will do. However, it was not my favorite film (and I’ll tell you why).

First, the reasons why it is top to bottom superior to all its rivals. The performances are roundly magnificent. These actors portray depth of feeling, inhabit their characters with ease, and present huge transformations. The screenplay is practically a vault-sealed jewel at a museum. It is clean, wastes no space, and bears no signs of anything but the highest art. The cinematography? Yeah…gripping. Black and white used to pristine effect. The narrative itself? Timeless and yet specific. Need I go on?

Look, Roma is like yoga or meditation, my friends. You have to READY yourself for it. You need to get yourself in the right “head space.” It is a two-plus hour journey of the heart, and as such, it demands all of your attention. If you don’t put the kids to bed, holster those stupid social media devices, dim the lights, and clear your mind of the endless distractions that vie for your attention, you’ll miss its raw power. Roma is cinema in the grand tradition of glory days past (Someone smarter than me could present all its historical touchstones, many of them foreign. For starters, Fellini and di Sica come to mind). Roma starts slow (almost alarmingly so), lets you take a peek around at its surroundings and get cozy in the characters’ skin. Then it builds slowly – more, a little more…and some more, until you’re entirely immersed. You’ll finish it, dab your eyes, and take a step back, finally seeing this MASSIVE narrative arc. The final forty five minutes were well worth the first hour and a half. You see how each scene built upon the last, how each character interaction was heading somewhere specific. And you get this incredible juxtaposition where the director is telling this minutely specific story of one family against this enormous cultural backdrop (in this case, the Colonia Roma district of Mexico City amidst protests, the paramilitary Los Halcones and the Corpus Christi Massacre). This is the work of a master auteur. That is the genius of Alfonso Cuaron.

I think that when people criticize Roma they really miss one fundamental truth about its creation: This is essentially a love letter from Alfonso Cuaron to his childhood nanny. It’s freaking dripping with pathos in that regard, and Cleo (played remarkably by Yalitza Apiricio in her FIRST acting role) is the target of much of his affections. The film begins visually by demonstrating what is Cleo’s typical routine – all work and little play. She washes dog crap down the drain outside, cares for her employer’s children like they are her own, and does various menial household chores. It’s REAL tedious work, so of course it feels belabored in the telling. She’s mostly ignored by the family matriarch, but is generally criticized whenever the lady of the household deigns her worthy of any speech. When she does get out to play, she falls prey to the wiles of a moronic youth hellbent on his own destruction. He too sees her as discardable. She is anything but, however, and the conclusion of the picture makes this emphatically clear.

The other key thing that Cuaron does in Roma is to show the immense strength of women. Nearly every male character in the story is either a bumbling idiot, a selfish cheat, or an incapable doctor. Conversely, the two women are bulwarks of strength. Scene after scene depict this in jaw-dropping fashion. A few will suffice. There is the sequence where a large group of youth are outdoors attempting to replicate the posture of a martial arts master and failing miserably. All except Cleo, who stands eye closed, perfectly in balance on the sidelines. Or the evolution of the matriarch, who finally getting out from under the oppression of her husband, takes the family on a meaningful vacation. She communicates openly and honestly about the family’s strife, and together they share the pain. It is a HUGE moment in a tiny, intimate space. Or the final scene which I do not wish to give away, but was about the best cinema has to offer. The humble nanny finally getting her dues for her courage, grit, faithfulness, and consistency.

As a parsed piece, it can be argued that Roma is really nothing spectacular. It is slow, somewhat muted and almost appears to peddle its wares in the mundane. But taken as a whole, Cuaron has conceived, written, edited, and shot an empathetic ode which finds the grandeur of every conceivable moment. Please check this one out. Today. As a look at power dynamics, class, gender, politics, but most of all as a love letter, it is nothing short of a masterpiece.

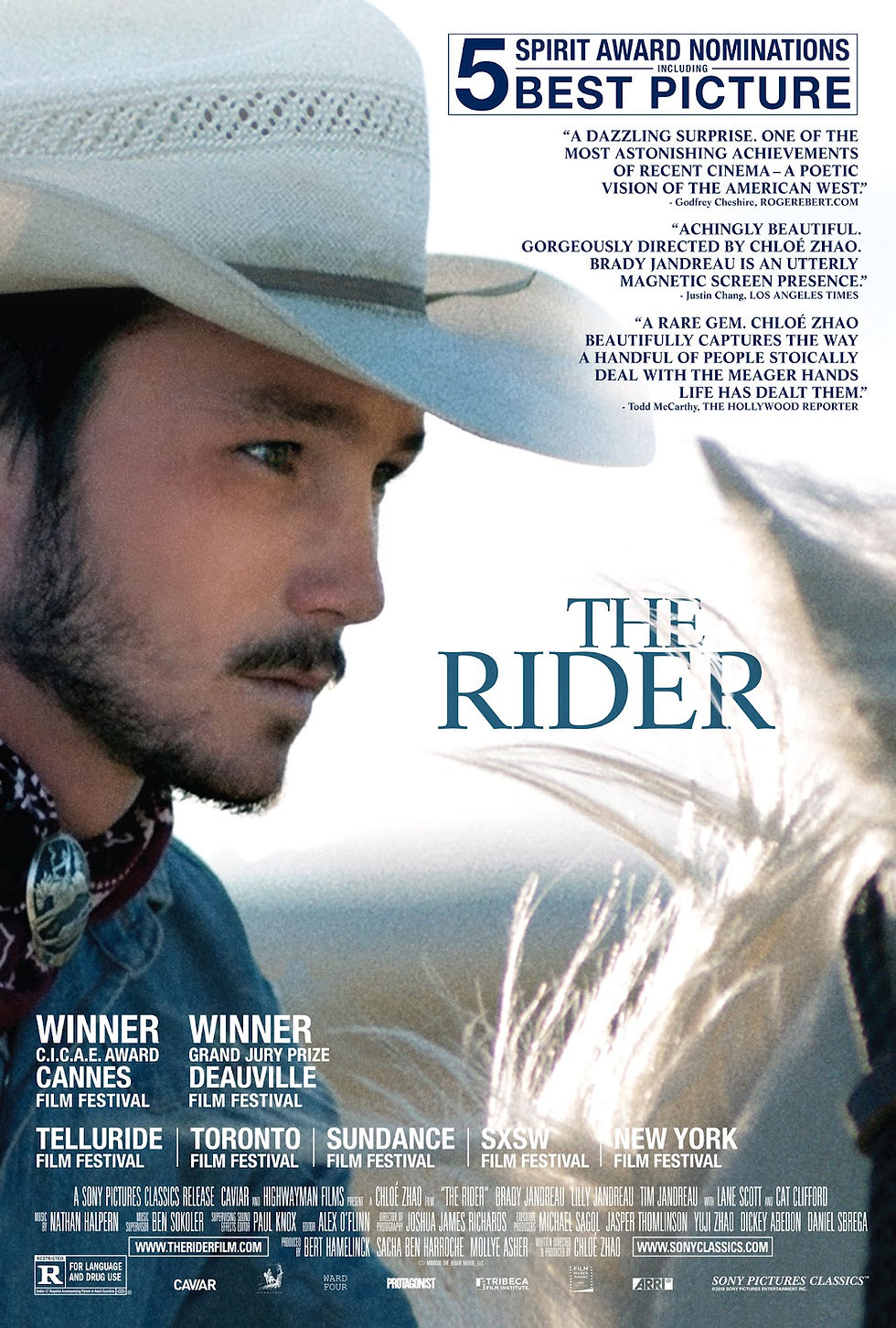

#1 The Rider

On paper, The Rider simply does not work. In fact, it’s almost oxymoronic. An Asian woman crafting an emotional journey about life in the heartland of America. A story, in fact, about what it really means to be a man, or masculinity, in the storied American Western tradition. And doing so using non-professional actors playing essentially what are fictionalized versions of themselves in their own native settings. All of this is risky as all get out, and apt to fall flat on its face. Instead, it’s an undeniable work of genius.

The journey to The Rider for director Chloe Zhao really began on the set of her first film on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation of South Dakota. While there, she met the real life Brady Jandreau, a dweller on the reservation who was a somewhat celebrated bronco. However, after falling and sustaining a serious head injury during a rodeo competition, Brady was left literally trying to get “back on the horse.” Clearly, Zhao saw this as a story rife with opportunity, and so she utilized the entire Jandreau family and other real-life rodeo folk from the area to tell her tale.

There is much to celebrate about The Rider. For starters, Zhao makes the brilliant move of eschewing any sort of “inspirational narrative” or anything Lifetime-y, opting instead for a simpler character study. Largely because of this, her story is often poetic, but not in a brazen or pretentious way. This is all the more the case because, as it would fortuitously turn out, Jandreau inhabits his own fictionalized skin REMARKABLY well. He is soft-spoken, largely un-emotive, and yet he oozes empathy from his very being. It is rare indeed to see such a stoic character create such an intense well of feeling or take us on such an emotional journey. But Jandreau does just this, and Zhao’s lyricism is brought forth all the more vibrantly by her cinematographer, Joshua James Richards. While the plains are long and oft forgotten on the “American scene,” they are unspeakably beautiful terrain. Richards shows us this through incredible shots of landscape and bright vs. fading light throughout the film. In Zhao and Richard’s hands, what could have easily become a mumblecore docudrama morphs into a film of astonishing beauty.

Beyond the shots and performances, individual scenes are simply magnetic. Brady often ventures out to visit a long-time circuit friend, Lane Scott (playing himself), who was a terrific rider in his own right before becoming paralyzed in a horrible accident. The sequences with Jandreau and Scott will just leave you in a puddle. They’re the most HUMAN film got for me all year long. Lane demonstrates his still positive humor and spirit through witty sign language and Brady matches him with jaw-dropping compassion. Moreover, Brady’s real life sister Lilly, who has a mental disability, offers some of the sweetest and laugh out loud tender moments of the entire picture in her interactions with her brother. She too is presented with exquisite care. And lastly, Jandreau demonstrates his staggering expertise with a horse, in a scene where he actually calms a bronco with extreme precision. Zhao just turns on the camera and lets it roll. It is simply breathtaking to watch.

But this is, after all, a story about masculinity and purpose, and what it means to be a rodeo star when doctors have told you that another head injury could turn you into a “vegetable” for life. Jandreau’s mind oscillates back and forth on this quandary throughout. He is as shaky about his future as is his right hand, which trembles as a constant reminder of his injury and the plate in his head. Scenes depict this struggle with his other friends, as they together search for a sense of purpose. Brady even seeks other employment to compensate for his distant drink and gambling-loving father. All of this finally comes to a head in a scene where he at last wears his emotions on his sleeve, and the tears feel crushingly poignant and yet contain the slightest glimmer of hope. The Ridermost of all to me is a poem, one with human players, light, landscape, shifting moods and a haunting exploration of masculinity in the modern West. THAT is why it was my favorite film of the year.

Comments